Dedicated to the thousands of children who need to improvetheir reading skills, and to their parents who want to help them succeed.

The sun did not shine. It was too wet to play.

So we sat in the house all that cold, cold, wet day.

I sat there with Sally. We sat there, we two.

And I said, "How I wish we had something to do!"

-from The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss -

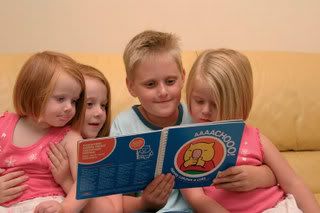

Thirty-eight percent of all fourth graders in the United States can't read this simple poem. Is your child one of them? Does your child drone, hesitate, and torture words while reading? He or she is one of 7 million elementary-aged children who is performing below his or her reading potential.

Certainly millions of children in America can't be stupid, lazy, or have ADD. Children sitting in the best classrooms in the country struggle with reading. Moms and dads are scratching their heads wondering whether to get a part-time job to pay for tutoring for Jerome or Ashley.

This past decade, educators have been fighting a Phonics versus Whole Language reading war. Each side has strong advocates, yet many children still emerge from schools unable to read. Meanwhile, scientists have been busy trying to identify the missing puzzle piece of how children learn to read.

Here's some good news: Research indicates that 90 to 95% of all children can learn to read at grade level with proper intervention. You can make a profound difference in your child's ability to read by spending fifteen minutes per day with your son or daughter, using information provided in this website, playing games and reading good books together.

From : www.succeedtoread.com