In ancient India, the Sanskrit grammarian Pāṇini (c. 520–460 BC), who is considered the founder of linguistics, in his text of Sanskrit phonology, the Shiva Sutras, discovers the concepts of the phoneme, the morpheme and the root. The Shiva Sutras describe a phonemic notational system in the fourteen initial lines of the Aṣṭādhyāyī. The notational system introduces different clusters of phonemes that serve special roles in the morphology of Sanskrit, and are referred to throughout the text. Panini's grammar of Sanskrit had a significant influence on Ferdinand de Saussure, the father of modern structuralism, who was a professor of Sanskrit.

The Polish scholar Jan Baudouin de Courtenay coined the word phoneme in 1876, and his work, though often unacknowledged, is considered to be the starting point of modern phonology. He worked not only on the theory of the phoneme but also on phonetic alternations (i.e., what is now called allophony and morphophonology). His influence on Ferdinand de Saussure was also significant.

Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy's posthumously published work, the Principles of Phonology (1939), is considered the foundation of the Prague School of phonology. Directly influenced by Baudouin de Courtenay, Trubetskoy is considered the founder of morphophonology, though morphophonology was first recognized by Baudouin de Courtenay. Trubetzkoy split phonology into phonemics and archiphonemics; the former has had more influence than the latter. Another important figure in the Prague School was Roman Jakobson, who was one of the most prominent linguists of the twentieth century.

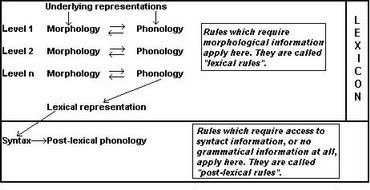

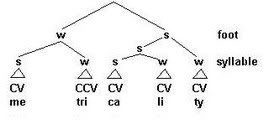

In 1968, Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle published The Sound Pattern of English (SPE), the basis for Generative Phonology. In this view, phonological representations (surface forms) are structures whose phonetic part is a sequence of phonemes which are made up of distinctive features. These features were an expansion of earlier work by Roman Jakobson, Gunnar Fant, and Halle. The features describe aspects of articulation and perception, are from a universally fixed set, and have the binary values + or -. Ordered phonological rules govern how this phonological representation (also called underlying representation) is transformed into the actual pronunciation (also called surface form.) An important consequence of the influence SPE had on phonological theory was the downplaying of the syllable and the emphasis on segments. Furthermore, the Generativists folded morphology into phonology, which both solved and created problems.

In the late 1960s, David Stampe introduced Natural Phonology. In this view, phonology is based on a set of universal phonological processes which interact with one another; which ones are active and which are suppressed are language-specific. Rather than acting on segments, phonological processes act on distinctive features within prosodic groups. Prosodic groups can be as small as a part of a syllable or as large as an entire utterance. Phonological processes are unordered with respect to each other and apply simultaneously (though the output of one process may be the input to another). The second-most prominent Natural Phonologist is Stampe's wife, Patricia Donegan; there are many Natural Phonologists in Europe, though also a few others in the U.S., such as Geoffrey Pullum. The principles of Natural Phonology were extended to morphology by Wolfgang U. Dressler, who founded Natural Morphology.

In 1976 John Goldsmith introduced autosegmental phonology. Phonological phenomena are no longer seen as one linear sequence of segments, called phonemes or feature combinations, but rather as some parallel sequences of features which reside on multiple tiers.Government Phonology, which originated in the early 1980s as an attempt to unify theoretical notions of syntactic and phonological structures, is based on the notion that all languages necessarily follow a small set of principles and vary according to their selection of certain binary parameters. That is, all languages' phonological structures are essentially the same, but there is restricted variation that accounts for differences in surface realizations. Principles are held to be inviolable, though parameters may sometimes come into conflict. Prominent figures include Jonathan Kaye (Linguist), Jean Lowenstamm, Jean-Roger Vergnaud, Monik Charette, John Harris, and many others.

In a course at the LSA summer institute in 1991, Alan Prince and Paul Smolensky developed Optimality Theory—an overall architecture for phonology according to which languages choose a pronunciation of a word that best satisfies a list of constraints which is ordered by importance: a lower-ranked constraint can be violated when the violation is necessary in order to obey a higher-ranked constraint. The approach was soon extended to morphology by John McCarthy and Alan Prince, and has become the dominant trend in phonology. Though this usually goes unacknowledged, Optimality Theory was strongly influenced by Natural Phonology; both view phonology in terms of constraints on speakers and their production, though these constraints are formalized in very different ways.